The aesthetic of the future is dead

The iPhone. Seamless, reflective, cool to the touch and enigmatic in its lack of expression. In its otherworldly appeal and promise of infinite possibilities, Apple’s design aesthetic captured the impossible: the digital made physical. This aesthetic of sci-fi minimalism and futuristic elegance – the digital code – has for decades been the visionary fantasy of human progress.

Today, that fantasy is reality.

The digital code does not promise a better future anymore. In fact, it represents a dystopia where we don’t control our devices, but they control us. When our devices are designed as black boxes, it does nothing to alleviate our lack of understanding of the technology we are intimately relying on.

With the current big-tech backlash around privacy issues and the urge to “disconnect” for fear of what technology is doing to us, we are in need of a new visual and material language that would help us feel at home with our devices. Our technologies and tools shape us like we shape them, and thus there can be great power in design actions. In his book Make it New: A History of Silicon Valley Design (2015) Barry M. Katz posits that it is design that has always “provided the bridge between research and development, art and engineering, technical performance and human behaviour”.

We believe that the winners of the future are those who through design language and form re-forge a meaningful, positive relationship between humans and technology. For in the everyday, it is the physical manifestations of digital ideas that shape our relationship to technology – and ultimately, to our future.

The digital code: how a design aesthetic became dominant

For a design aesthetic to reach the cultural zeitgeist, it needs to have a deeply founded philosophy of design that responds to a cultural need. In his book Image, Music, Text (1977) Roland Barthes, the French cultural philosopher, likens design to myth – for both are media for storytelling that represent and shape cultural truths and their human meaning. In order for design to shape cultural meaning, its philosophy needs to hit the nerve in given social, economic and cultural structures.

When the iPhone was released in 2007, its symbolic and aesthetic qualities reflected perfectly the cognitive and social context of the Western world, and thus captured the hearts and minds of a generation. For a world aspiring for increased mobility and networked connections, the iPhone was the answer.

The messianic speech given by Steve Jobs at the iPhone launch acknowledges this. Those who were present at the launch (as well as the millions who have viewed it online) can recall how Jobs came on stage and declared that “Today, we are going to reinvent the phone!” as a sublime light shined behind the company’s logo. However, even long before the iPhone, Apple had been known for its technological prowess. The apple in Apple, with its chunk missing, cheekily calls back to humans’ perilous desire for knowledge and progress in a reference to the mother and father of rebellious emancipation, Adam and Eve.

For the past centuries, the dream of the Western world has been to transcend our bodies and reach a blissful state of knowledge and purpose. Humanity has worked towards those better futures through technological development. For in developing new technologies, we improve our own capacity to do more, to learn more, to better ourselves.

The iPhone offers high levels of functionality, ease and simplicity, with no time wasted on romantic appeal or tactile qualities. At the time of its release, the fluidity and otherworldliness of the perfected glass and chrome rectangles promised a better world in the digital future. The internet had already opened the door for a possibility to rethink who we are by transcending location, ability, race, gender. The iPhone put that in our pockets, promising that digitalisation would transcend humanity from their material condition, abstract them from time and place, for good.

The digital code does not promise a better future anymore.

In his online essay Digital Dualism versus Augmented Reality (2011) the sociologist and social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson introduces the concept of “digital dualism”: the belief that the digital world is “virtual” and the physical world “real”. This concept is central to the ontology behind Apple’s design philosophy. The magical iPhone allows us “real” beings to blend into the “virtual”, allowing us to truly master our universe.

The iPhone became the icon of the digital code, and its design aesthetics were replicated across major consumer electronics brands and spread from cosmetics to food packaging and jewellery. Still today, the iPhone sets the design direction of consumer electronics for the year coming in their annual Autumn launches.

Building a design aesthetic that lasts

For a design aesthetic to stick rather than be a fleeting trend, it needs to be situated on the continuum of aesthetics past, present and future. A resonating aesthetic is hardly spontaneously occurring, but a product of previous art and design. Indeed, the iPhone’s success does not stem from miraculous “out-of-the-box” thinking, but a deep understanding of design. Design that builds on the social and cultural aesthetic – whether it rejects, updates or evolves – is intuitive and purposeful, and is easily adapted as part of everyday rituals.

The roots of iPhone’s design aesthetic can be traced back to the beginning of the 20th Century, particularly to the movements of Futurism and Modernism.

Futurism’s influence on the digital code is undeniable. In the beginning of the 20th Century, with the rise of industrialization, the belief in technological progress’ ability to emancipate the human race had unprecedented proof. Human capacities rapidly expanded beyond imagination, leading to technological utopianism – the belief that technology can solve any problem humanity faces.

Technological utopianism found an aesthetic in Futurism, introducing the fetishization of technology and progress to art and literature. Traditional art forms like painting and sculpture drove the change towards the “Machine age” that would renew consciousness through the aesthetics of speed, progress and industrial development. The newly popularised mediums of photography and cinema brought to the mainstream fever dreams where machines, steel and fire speeded humans to the future. The birth of popularised science fiction can be traced back to 1927 when Metropolis, the first ever feature length sci-fi film premiered. Today the film is an icon, but when it originally came out, the eroticised Maschinenmensch was greeted with suspicion.

Nevertheless, from there on the aesthetics of the future have been defined by the materials linked to industrial progress – chrome, shiny glass, stainless steel, electronic bright colours – and a hard-boiled belief in the perpetual future. Apple lives by this cultural myth with their constant updates both in hardware and software that force renewal – think of the removal of the headphone jack in recent models that pushed people to wireless listening, or the software updates that eventually clog up the memory, pushing people to larger capacities. The iPhone aesthetic religiously replicates these dreams with its materials; glossy glass backs, metallic hues, inorganic colours and a growing lack of tactility, reminiscent of the un-embodied nature of virtual space.

Industrialisation also gave birth to the second key influencer of the digital code – the Modernist movement in design. What separated Modernism from previous arts and crafts movements was how it prioritised functional requirements instead of traditional aesthetics. As a result, Modernist design was simple and clean, based on rationality and functionality, always aiming for a seamless and purposeful experience.

In Modernism, everything that is not necessary, stands in the way of progress. In his 1908 essay Ornament and Crime, the influential architect and designer Adolf Loos states that “ornamentation represents wasted labour and ruined material”. Loos’ radical aesthetic purism attributes cultural evolution to purity of form, seeing ornamentation as childlike and primitive, a “phenomenon either of backwardness or degeneration”. Purity of form represents the essential, superior in its freedom from distraction.

Modernist ideals carried on through the century: in architecture, most notably in the Bauhaus movement, and in industrial design, in Functionalism. The simplicity and seamless purity of the iPhone is a direct descendant of Modernism. Dieter Rams, a famous Functionalist designer, laid down ten principles of good design still widely recognised today. He determined that the measure of good design is how effective and simple it is: good design should be unobtrusive, always neutral and restrained. Think of the iPhone X as the zenith of the digital code, bezel-less as if nearly blending in to virtual space, becoming so simple and essential that it’s close to disappearing altogether.

The simplicity of the hardware is replicated in the software. The iPhone uses Flat Design Language for its user interface, a design interface language that is a direct descendant of the Bauhaus movement. First adapted by Microsoft in the early 2000’s, flat design uses minimal 3D elements, such as shadows or textures. Later, both Apple’s and Google’s operating systems adopted the same design language, dropping skeuomorphism – a design language that retains ornamental design cues.

Today, all major consumer electronics use Flat Design UI. The popularity of flat lay pictures is a testament to how, when a design aesthetic is intuitive and purposeful, it evokes meaning and is adopted and appropriated by people. This, in turn, guarantees its longevity.

What then? The oversaturation of an aesthetic

There comes a time when an aesthetic becomes so widely adapted that it starts to lose aspirational meaning.

The iPhone X is the logical conclusion of the Western obsession with formal purism – an item so simple and perfect, it seems otherworldly, god-like. The boundless design reflects its miraculous technological qualities – it is the rightful tool for homo universalis, the renaissance man whose knowledge knows no boundaries.

Today, the dream of the digital has been realised, the aesthetic seeping everywhere. The digital code does not signal a future anymore, it has become the status quo. It reflects the desires and needs of a bygone era, where digitisation was only a fantastical dream – not a mundane reality.

Today, we can connect across the globe, experience places and things away from our physical reality, appear as whatever we wish in online communities. Yet we humans, even now that we live in a digital world, cannot escape our analogue selves. The way we interact with the digital, what shapes our relationship to it, will always be somehow embedded in the material world. And that material world together with our embodied selves is a large part of how we create, learn, communicate, and feel.

What lies behind the sleek, glassy surfaces of the iPhone is a whole philosophy about technology – an ontology of what technology means to humans now shared and disseminated globally through consumer electronics and beyond. But that philosophy, the philosophy behind the digital code, does not respond to our cultural needs anymore.

We face altogether different issues today that the digital code is unable to respond to. With growing computation speed and ever improving nanotechnology, we are questioning the reason for our existence. We struggle simultaneously with boredom and meaninglessness as well as information and stimulus overload.

The digital code does quite the opposite of helping. Consumer electronics are fetishized, adorned, treated as sacred objects. We protect them with casing, we wipe their screens so that our greasy fingerprints that reveal our embodied self, won’t show. We hold them at the end of our fingertips, delicately, always taking care that they do not fall.

Our devices have become the object of attention. Ever multiplying and largening screens demand our time with push notifications and pulls-to-refresh. The use-object has been transformed into a kind of phantasm whose existence is a psychological projection of our quest for meaning, estranged from its social and embodied reality. As a consequence, devices start feeling inhuman, cold and scary rather than sublime and otherworldly.

In order to not feel subservient to our technology, we need to find a different aesthetic of our future. The response outside tech has been the return to the “real”. A testament to this is the emergence of DIY-culture in fixing your own bike, scrapbooking, making craft beer and pickling, being an explorative cook and a forager.

However, “authenticity” as a trend is not a long-term strategy for technology. Nostalgia for better times is not progressive like technology inherently needs to be. In the long run, we do not want to just reference the design character of historical non-commodity modes of production (“craft”) and paint them on modern ones (a wooden cover on an iPhone).

Instead of falling to technophobia or neo-Luddism and shunning the technological in pursuit of the mythical “real”, we should keep looking forward. We should break out of the ontology of digital dualism and stop seeing the “virtual” and the “real” as separates.

Spotting signs for a new design philosophy

Rather than valorising the “virtual” over the “real” or vice versa, future aesthetics need to balance and play with different aesthetic cues and find a way to co-exist.

There are some signs of a paradigm shift already in technological innovation. The newer MacBooks take a step into the analogue world. Instead of their trademark keyboard that glorifies the seamless, effortless typing, the latest in the series are characterized by their clunking sound. This evokes the analogue world of a typewriter, asserting the creativity and productivity of the individual.

The fluidity and seamlessness of the digital code is also being challenged in the way technology is operated. Sound and touch are challenging the supremacy of vision as the primary sense of being-in-the-world. All big tech companies are innovating around voice controls, rather than screens and buttons, recognizing the naturalness of speech for humans as well as its inherently social role in comparison to the individualism of screens. Touch, too, is becoming more recognised when innovating with materials and more sensitive haptic cues.

Turning signs into typologies and guidelines

To evolve our relationship to technology, it is crucial we address the paradigm shift on the level of design aesthetics and language. The task is still to make the abstract understandable and relatable, in other words, to make the invisible visible.

Armed with a different philosophy of time, space, and cognition, we can design a different future. In the end, it is designers who give shape to our technological dreams, who shape into being the immaterial by creating physical manifestations of it.

The winners of the future are those who through design aesthetics and language re-forge a meaningful, positive relationship between the “real” and the “virtual”. As Dieter Rams observed in his essay Omit the Unimportant (1989): “Our culture is our home. It would be a great help if we could feel more at home in this everyday culture, if alienation, confusion and sensory overload would lessen”.

By identifying design typologies from the world of technology and design today, we can begin to decode the intuitive form of an aesthetic, and generate guidelines to purposefully build towards an inspiring and future-proofed aesthetic. Here, we have identified and described three typologies with some key examples.

1. Organic tactility

Organic tactility downplays the other-ness of technology, instead valorising the organic. It uses natural shapes, textures and colours that are responsive to the touch, comforting in their familiarity from the natural world. The designs are not highly finished and polished, but an aesthetic designed to engage the senses beyond the visual. Hand-touched signifiers evoke safety, security and humanity.

- Google Home emulates a stone in its form and uses a textural finish to soften the look and help it blend into surroundings

- Muji x Ladies and Gentlemen studio installation at New York Design Week 2018 explores the design ethos of minimalist Muji, focusing in on its honest materials.

- Native Union uses raw materials like marble finishes and textured layering on devices and appliances to bring a grounded aesthetic and feel to technology.

2. Empathetic functionalism

Empathetic functionalism over-emphasizes technology in an irreverent and playful way. The retro-analogue code emphasizes human agency and creativity. The primary-colour and overtly simple, matte aesthetic reflects the curiosity and empathy of the designs, rather than positing them as tools for superiority or conquest. The bold and cute signifiers cue innocence, optimism and cosiness.

- Fujifilm Instax presents an analogue alternative to Instagram. It re-asserts the joy and expressiveness of the photographic moment by departing from a generic high-tech aesthetic of precision and technical finesse.

- Nokia’s re-introduction of the 3310 has a rounded, empathetic design and bright, optimistic colours.

- The lofree keyboard design recognizes the importance of tactile response to actions, and its matte colour palette brings a cosy, soft feel.

3. Bionic beauty

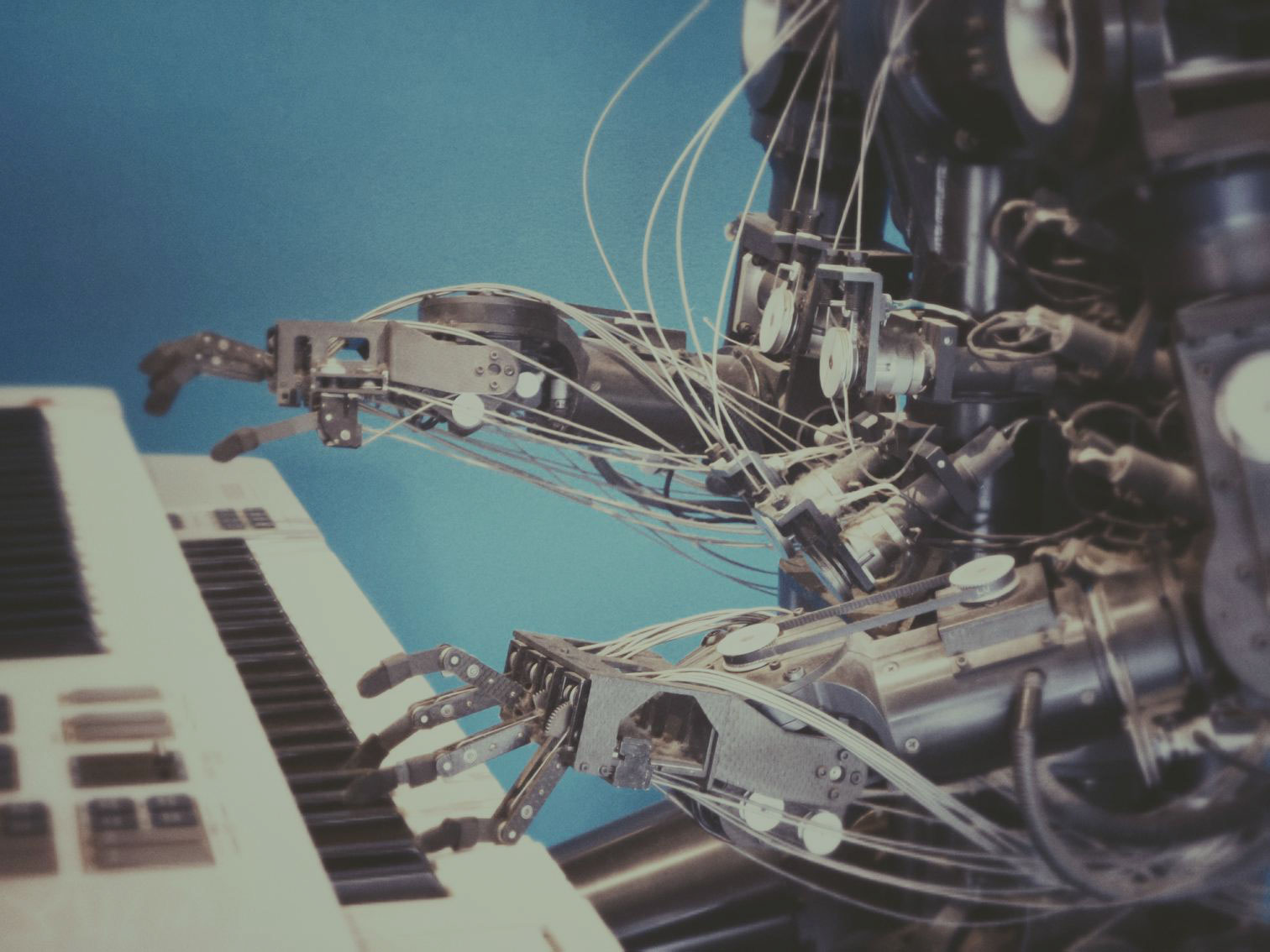

Bionic beauty emphasizes the likeness of the natural and the scientific, going back to roots of renaissance where art and science were not seen as separate. It replicates ecosystems and models of the natural world in biomimicry. The signifiers mixing the real and the synthetic evoke curiosity, progress, and sustainability.

- The conceptual designer Lola Gielen’s Neo is a tactile musical instrument. “Music is a sensory experience, while playing a traditional instrument sound is directly influenced by touch. This is often lost in digital instruments. Even though Neo is a digital instrument, your touch will still influence the sound”.

- Adidas Futurecraft 4D + Studio Hagel sneakers use a 3D-printed midsole. The cutting edge technology replicates natural processes in mass manufacturing by moulding liquid with light and oxygen. This gives designers unprecedented opportunities in terms of material design, celebrated in the collaboration with Studio Hagel’s re-imagination of the shoe.

- Patch, by designer François Chambard / UM project, is a project featuring interconnected furniture that makes electricity visible and part of natural design, offering an alternative to the current smart home designs.