This week, Jun Lee tells us about his role as a partner at Gemic, the importance of technology to the human experience, and why, going forward, the most successful companies will enable people to craft their own narratives and tell their own stories. Jun believes that narrative reached an inflection point in the 21st century with the rise of reality TV, where strong storytelling lost out to personality-driven content. In order to be successful now, he says, it’s time to put our faith back in building narratives.

To start out, could you tell us who you are and what your current role is at Gemic?

My name is Jun Lee and I’m a partner at Gemic.

In your work at Gemic, what kinds of questions do you focus on?

I’m interested in our relationship with technology and how it modifies and alters the experience of being human.

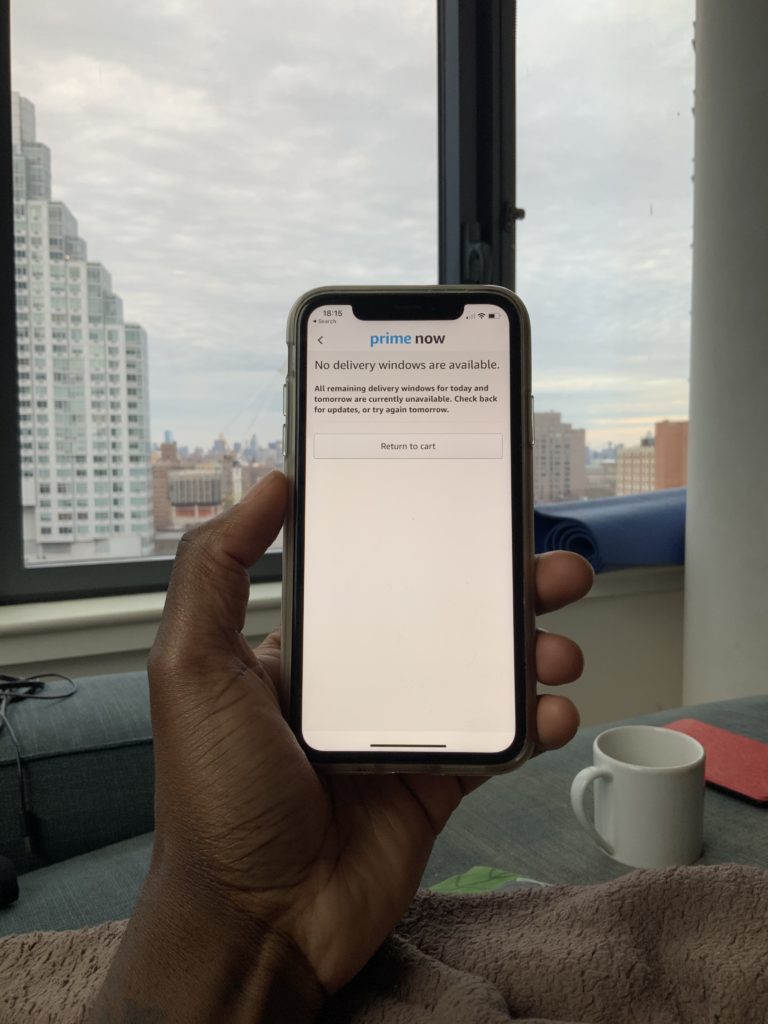

Something like the smartphone, for example, has insinuated into our everyday lives in profound ways. It’s eliminated the need for detailed planning from everyday life and has allowed us to be much more spontaneous.

So you think what’s more important is how technology changes us, rather than how we use it.

Yes, and it also changes the way we think about ourselves, about how we spend our time, and how we prioritize and delegate power and influence. Understanding technology is as important to understanding modern life as understanding food, health, work and family.

When did your interest in technology start?

When technology research switched from “what technology can do for us” to “what technology does to us”. I worked with someone who really inspired me to think about these questions differently than I had before.

Is there one seminal work that changed the way you think about the world?

The Real World on MTV.

That’s an interesting choice! Why The Real World?

Actually, it was the combination of The Real World, Cops, and Jerry Springer. They changed my view on the rules of narrative. These shows changed norms around what is a story and who creates stories. Effectively, it was a starting point for everything that we think about when it comes to social media and popular culture today.

What we see in pop culture now is a shift – from an interest in narratives to an interest in personalities. A simple way to put it is, we’ve entered an era in which total strangers can be subjects of deep interest. In the past, stories were the subject of interest and those stories were told by narrators and storytellers who had established themselves as both skilled artisans and, to a degree, institutional authorities.

In modern society we see a shift toward individualism, or individual experience, as the primary interest. When it comes to this sense of prioritizing individual values over communal ones, The Real World was the earliest signal of what we talk about as modern life.

What’s one big idea or shift you think everyone should be talking about?

I’d say the topic I get the most inspiration from right now is this gradual shift to individual narratives.

Something I’m curious to understand is how we’ve taken apart traditional forms of narrative, and I’m not sure if we’ve figured out how to put them back together.

Jun Lee, Gemic Partner

I’ll give an example: we all find ourselves in what we call doom scrolls or those infinite stimulation loops. To use a food metaphor, it’s the equivalent of replacing your entire diet with appetizers. All content has been created to engage people, but its limitation is that it’s designed to entice you.

Right, versus being designed to ‘nourish’ you or your mind?

The experience that we call exhaustion that comes from engaging with this kind of content is a result of the lack of a ‘beginning and end’ structure that used to define our media experiences. With this kind of short form content, there’s no real defined beginning or end – they either continue endlessly until they stop randomly, or become infinite variations on a theme. They are riffs, in the world of music or sketches — they’re things that are not complete.

Consuming that as our primary form of entertainment or intellectual material leads to a fairly unhealthy mental state. There are some analogies here to good nutrition and diet, which is formed around a cyclical process of hunger and nourishment – you become hungry, you eat, you’re satisfied and that repeats each day. This kind of defined cyclical process doesn’t really exist in our current consumption of media. It’s just a life of snacking.

This is also why you’ll see people going on “intermittent fasts” from social media or detoxing from their phones. You have to structure your own media experience, which is difficult to do.

What are the business implications of this idea?

Narratives shape our culture, politics and consumption behaviors. Today, we are awash in narratives that are the result of a lot of trial and error, experimentation and do-it-yourself ingenuity. While we may have empowered everyday people to tell their own stories, the results are really mixed. We talk about creating technologies that enable more people to tell their stories, but the reality is that most of these stories are not very compelling and worse, create a lot of noise, hype, scandal and anger without adding any cultural or social value.

The irony is that those people who are self-taught. and able to produce compelling stories, are identified and brought into the world of professional storytelling. Many of today’s celebrated musicians, screenwriters and directors who people celebrate as modern self-taught storytellers are now in the professional storytelling business.

There’s an opportunity to help people participate in narrative creation – and also get better at it. They need to be given the tools to build narratives for themselves – narratives that help them engage socially and economically benefit from their efforts.

Jun Lee, Gemic Partner

Before we’re done here I want to ask you about Gemic generally – what do you think of Gemic’s role in the world?

The way I think about what we do and how we think is that we offer a non-technocratic approach to thinking about human systems.

What do you see as the drawbacks of a technocratic approach to studying human systems?

A technocratic view is kind of a distant analysis of the different layers of a system. It’s a dispassionate approach — the ideal outcome of this kind of thinking is that the researcher is a dispassionate observer. You look at the world as if you have no stake in it, or that you don’t really care what kind of outcome is going to come about.

I would say that our role is to offer a different way of looking at the world. We lean heavily on a cultural and human lens. We examine how people decide to be and what they decide is good. And we think that human values should be the lead horse and that we should bet on it.

So we offer a human systems view that is the opposite of a technocratic view. We lean heavily on the cultural perspective to both assess and diagnose what’s happening in society – and to successfully route it to a place where we want it to go. We’re using systems in a more motivated way to achieve cultural outcomes that we think are fit for people, fit for society, and that bring us closer together. It’s a biased view of the future with people at the center.

What will the next year hold for Gemic, and for you at Gemic?

We’re always trying to find new ways of understanding the world and explain what’s going on. We are busy, we’ve been growing, and we’re taking on a lot of different topics. We like to cycle between doing research grounded in real-world experiences and then reflecting on them more abstractly.

What have we learned and engaged with over the past year that has changed the way we think? Asking these kinds of questions helps us improve our approach, taking what matters and discarding what doesn’t. So I hope the next year will hold some of that reflection and growth.

Jun is a Partner in Gemic’s New York Office, where he brings 20 years of experience in research & product development with focuses in communications, digital media use, automotive mobility, and home life. His career has been defined by a desire to understand why people embrace, reject, and in some cases, appropriate technologies in unanticipated ways. At Gemic, this translates into a desire to help companies reimagine the ways technology might change how people work, socialize, and connect to one another. Jun has a Master’s degree in Design from the Institute of Design and a BA in Neuroscience and Behavior from Columbia University. He has lived abroad in Seoul and Copenhagen before returning to New York.